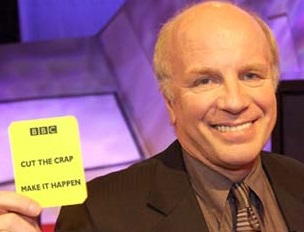

Popular misconceptions 3: looking back at DG Greg Dyke

Brian Butterworth published on UK Free TV

Brian Butterworth published on UK Free TV For today's bit of history, I have not taken a BBC publication, but a few select paragraphs from Greg Dyke: Inside Story eBook: [Greg Dyke: Amazon.co.uk: Kindle Store].

I have concentrated on three small extracts which deal with UK Free TV subject. I do recommend the book too, it is a great read.

Freeview

In my last two years as Director-General would make two moves that I believed were to the long-term advantage of the BBC and broadcasting in general in Britain, moves which would prevent BSkyB from dominating broadcasting in this country. The first was perhaps the most important decision I took in my four years at the BBC: the launch of Freeview.... After they had lost £1.2 billion of their shareholders' money, Granada and Carlton finally pulled the plug and ITV Digital went bust in early 2002.

But what really killed On Digital was that the technology didn't work. Only about 50 per cent of the population could get any sort of DTT picture, and less than a third of homes in the UK could get a clean, clear signal. ... one day, just before Christmas 2001, the Managing Director of Carlton, Gerry Murphy, whom I did trust ... honourably advised me ... he doubted where there was enough money to keep ITV Digital going. From that moment on we began to develop version two. We called it Freeview.

Our research had shown that there were a lot of people who wanted a wider choice of television channels but didn't want to pay for it... older and more middle-class; in effect traditional BBC viewers and listeners.

At a day's notice, I decoded to turn up at a seminar being held at Number 11 Downing Street and outline the idea for Freeview. It was probably the concept's turning point.

The pitch was pretty simple. Part of the reason ITV Digital had failed was the failure of technology: we knew how to fix that. They had also failed because they had gone head to head with BSkyB: we had no intention of doing that because this would not be a pay service. Finally, ITV Digital became involved in buying expensive rights: we'd avoid this because we were only proposing a distribution system in which the risk belonged to the channel providers. The great trick of Freeview would be to persuade consumers to buy the box and to see it in the ay they saw their television set. If it didn't work it was their problem, not ours.

Freeview was also important to the BBC defensively. Opponents of the licence fee always argue that once everyone can get pay television the licence fee as a means of funding the BBC will be unnecessary... Freeview makes it very hard for any Government to try to make the BBC a pay-television service. The more Freeview boxes out there, the harder it will be to switch the BBC to a subscription service since most of the boxes can't be adapted for pay TV.

Free satellite

The second move we made against BSkyB was a more obvious victory. When the BBC first put its television services onto BSkyB's digital platform it took the rather odd decision to pay BSkyB £5 million for the privilege of doing so. It was a decision taken back in 1998 and it was rather odd because BSkyB were desperate to get the BBC on board and would happily have paid them to get them. The BBC were total mugs.

The second move we made against BSkyB was a more obvious victory. When the BBC first put its television services onto BSkyB's digital platform it took the rather odd decision to pay BSkyB £5 million for the privilege of doing so. It was a decision taken back in 1998 and it was rather odd because BSkyB were desperate to get the BBC on board and would happily have paid them to get them. The BBC were total mugs.

In late 2003, two further things had happened. First, a new satellite had been launched with a smaller footprint that only covered the UK and part of Northern Europe. Second, I had discovered from my colleagues in the German equivalent of the BBC that they happily put their signals out unencrypted, even if that meant they were accessible all across Europe - this was allowed under European legislation on overspill.

This would bring real advantages to the BBC. In one move we'd be free of the BSkyB satellite monopoly; we would save lots of money; and, finally, our regional services would be available throughout the country.

When Carolyn Fairbairn and I first came up with the idea of going unencrypted, everyone else at the BBC told us why it couldn't be done... I thought they were behaving like wimps... My reckoning was that we represented half the free television market: who in their right mind was going to sell sports rights or movies without half the market? So despite everyone's fears we went ahead.

Predictably the US studios all got together to protest, but Disney came round the back and did a deal, so that was the end of that... the rest of them folded one by one.

In the sports area we were in the middle of negotiating a £280 million plus deal with the Football Association. When they said that it only a deal if our signal was encrypted our negotiators simply got up, said that there was no point continuing the discussion, as left. They were soon back at the table. We got the deal and our signal remained unencutped.

Then there was BSkyB's electronic programme guide. The ITC set up an investigation.... then I got a call from a mutual friend who said that Tony Ball at BSkyB, would like a chat.

Then there was BSkyB's electronic programme guide. The ITC set up an investigation.... then I got a call from a mutual friend who said that Tony Ball at BSkyB, would like a chat.

Over the next couple of weeks our conversations got friendlier still and we began to talk ... abut the possibility of what we called a regionalisation service. We wanted to make sure the right signals for BBC One and BBC Two went to the right regions in satellite comes and we were prepared to pay for that.

I became suspicious: we were getting too good a deal. BSkyB even agreed to move BBC Three to slot 115 and BBC Four to 116 on their programme guide, slots we'd been trying to get for years. And then it dawned on me. BSkyB were keen to get an agreement before the ITC adjudication.

It was very clear that the ITC had discovered something that would have been deeply embarrassing to BSkyB if it became public... To this day, I don't know what the ITC found, but I do know they found something.

Digital radio

Digital radio eventually took off in 2003 when radio manufacturer finally decided to produce digital radio sets and, surprise, surprise, found there was a great demand for them. Up until then the history of digital radio was a classic chicken and egg situation. The manufacturers wouldn't produce digital radios until there were more digital services available, and the BBC and commercial radio stations wouldn't fund new digital service until the manufacturer produces and sold enough radios. It was Jenny Abramsky, the BBC's Director of Radio, who broke the deadlock.

Digital radio eventually took off in 2003 when radio manufacturer finally decided to produce digital radio sets and, surprise, surprise, found there was a great demand for them. Up until then the history of digital radio was a classic chicken and egg situation. The manufacturers wouldn't produce digital radios until there were more digital services available, and the BBC and commercial radio stations wouldn't fund new digital service until the manufacturer produces and sold enough radios. It was Jenny Abramsky, the BBC's Director of Radio, who broke the deadlock.

Some days she is charming and reasonable; on others her paranoid that radio is a second-class citizen to televioisn within the BBC makes her difficult to deal with. Her augment is simply wrong; BBC radio station are probably the best funded in the world, and are significantly better funded than any competitors in Britain. For example there is not a radio station anywhere in the world that receives the £70 million a year it costs to run Radio Four.

Without her commitment to, and promotion of, digital radio it simply wouldn't have happened. She persuaded, cajoled and threatened everyone inside the BBC to support the plan to develop a series of new BBC digital radio services. And it was the arrival of those services that finally persuaded the radio manufacturers to start producing digital radios.

The BBC took the decision to spend £18 a year on a range of new digital radio services... it also meant spending many more million actually paying for the transmission system that would enable 85 percent of the population to receive digital radio.

There was no problem persuading the Secretary of State to approve the new radio stations because the commercial radio companies were actually in favour of BBC expansion. They wanted digital radio to work and knew that only the BBC was big enough to drive it.

Greg Dyke - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

All questions

In this section